|

Open Wheels, Dirt, &

Speed

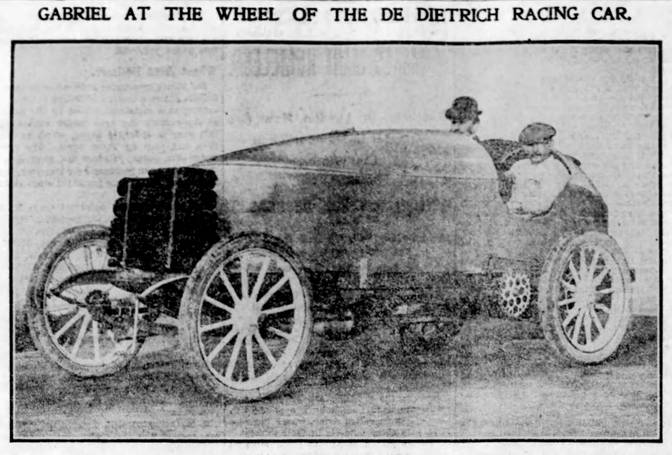

Pope-Toledo photo

Courtesy of the National Automotive History Collection, Caruso

photo from www.carusomidgetracing.com/racing-photos.html As

we've seen here recently, early 1900s life was not always slow for the

people of dusty This

is the first part of an Ancient

Hixtory article devoted to The

next part of this article, to appear in April's Ancient Hixtory, will look at different men.

Resourceful, ingenious, and dedicated, they worked to create a

world of racing for powerful but small cars.

Among them we will find Mike Caruso, a man who put down roots in *** The

Vanderbilt Cup Races In 1900, William Kissam Vanderbilt

Junior was 22 years old, and heir to an immense fortune.

He was also fascinated by fast cars.

He became convinced that American automobiles of the day were

inferior to those of

"Willie K," as his friends called

him, knew speed first-hand. In

January 1904, he set a new world record, driving his Mercedes

for a mile on the sands near Daytona at an average of 92.3 mph.

Tiffany and Co. depicted that feat on the trophy it created for

the fruit of Vanderbilt's musings, the Vanderbilt Cup Races, the first

of which rolled right through *** The

1904 Race State

of the Art In 1904, breakdowns were to be

expected. The automobiles of

the era were not reliable, and driving them long distances over rough

roads at high speed made things worse.

Thus, a race car had to carry a "mechanician." The Ford Motor Company was one year

old, and the Model T still

four years in the future, but other automakers were on the scene.

Only a few of those who supplied cars for the Vanderbilt Cup Race

exist today: FIAT, Renault, and Mercedes (no Benz

yet). The cars were not

standard models; each had unique quirks.

This uniqueness made the men in the passenger seats

indispensable. As they rode,

they were vigilant, listening and watching for any hint of problems.

They had stocked their toolboxes beforehand, trying to be ready

for anything they might need as the hundreds of miles sped by.

The The vehicles were fast, heavy, and

clumsy, with high centers of gravity.

Little was known about designing suspensions that could keep them

upright and controllable. Ruts

in dirt roads, excessive cornering speed, or blown tires could cause

roll-overs that threw or crushed the men in the cars to their deaths.

Even if nothing went wrong with a car, its mechanician might be

momentarily distracted by a problem, relax his grip on the car, and get

bounced headfirst to the ground. Spectators fared as poorly.

Despite frequent newspaper reports of cars' striking onlookers

at races, the public refused to believe that standing at the edge of -

or even on - the course, as close as possible to the trajectory of an

approaching car, was a bad idea. What

could go wrong? Anything.

More than once, a punctured tire diverted a ton of speeding steel

towards a cluster of spectators. The

Course The race consisted of 10 clockwise laps

around a 30.24 mile course, almost triangular in shape.

The points of the triangle were

The There were railroad crossings.

At Hempstead and The newspaper story excerpted below

relates how an LIRR train was cleared to proceed through a crossing

during the race, and promptly almost hit a speeding auto that failed to

stop for inspection. This

was not a matter of recklessness; the car's brake lines had failed as

it approached the control. So

as not to collide with the train, the driver sped in front of the moving

locomotive, with a very few feet to spare.

Once safely beyond the crossing, he slowed and coasted to a stop,

his race finished.

A

Fatality During the second lap of the race, the Mercedes

of driver George Arendt blew a tire at high speed near Top

Finishers After about five and one-half hours,

the contest ended very abruptly (see notes below).

French cars held the two highest spots, followed by an American

car. The winning driver was

described by the press as "an American millionaire."

*To

calculate average speed, one must exclude both the time spent not racing

in the controls, and the distance driven in the controls.

The speeds above were calculated from the published times and an

adjusted race length of 284.4 miles. **When

Heath's Panhard finished his last lap, no car still racing could

possibly beat his time except one - the Clement-Bayard.

As soon as Clement's final time was posted, the spectators saw

that Heath had won, and they ran down from the grandstand, flooding the

track. With the remaining

contestants still racing towards the finish, Willie K desperately ran

amongst the people, urging them to clear the course for their own

safety. Quick-thinking

officials telephoned others stationed around the track, stopping the

race immediately. The

standings from third place down were assigned according to where cars

stood at that time. Albert Clement's time made his the

closest second-place finish of any international road race to date, but

Heath's approach to the race had kept Clement closer than he might

have been. Heath tried to

balance his pace against the limits of his Panhard's endurance,

driving only as fast as required to maintain first place.

This strategy proved wise; another Panhard driver went all-out

from the start. He recorded

the fastest lap of the race - but during the fourth lap, his car's

clutch failed, and his race was over. Some highlights of the race can be

viewed on several YouTube

postings, including this one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zYoA4aTTyCE *** Beyond

1904 The race over, it was time for

Vanderbilt to revise his plans, for there had been many problems. The track record (no pun intended) of

European road racing was rife with serious injuries and fatalities, with

respect both to spectators and participants.

Casualties seemed to be unavoidable.

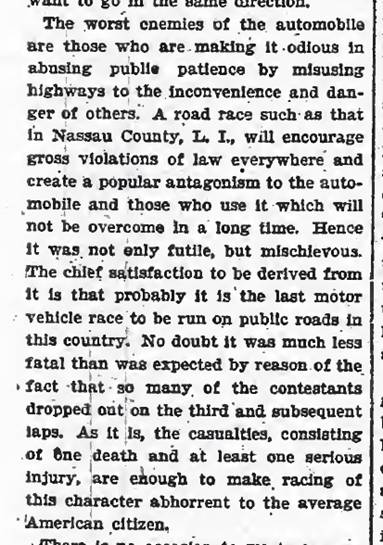

A number of people feared that the Vanderbilt Races had brought

the same problem to the

New York Times Editorial, October 9, 1904 Furthermore, closing public roads for

such an event had been met with legal challenges.

Some were based on individual cases (i.e., people whose

businesses or lives had been impacted by road closures).

Others were based on more abstract issues, e.g. should

taxpayer-funded public roads ever be closed so that wealthy

non-residents could race? There also had been ugly, unspoken

objections. The night before

the race, nails had been sprinkled on the track near the starting area,

causing numerous tire punctures. Worse,

a rifle had been fired blindly into a barn used as headquarters for one

of the racing teams; no one was injured, and the car was not

significantly affected. Apparently,

people in the "good old days" were not always innocent and kind. Willie K realized that the differences

between That was true in another way, too.

American country roads, although newer by millennia than their

European counterparts, were often unsuitable for ordinary driving, let

alone for racing. Hoping to

stir public support for road improvements, Vanderbilt undertook

construction of the Long Island

Motor Parkway, relics of which survive today.

Some of it was used later in the Cup Race series, as a safer

alternative to public roads along the southern leg of the courses. *** Return

to The

Course Note that I deliberately ended the

previous paragraph with the word "courses," plural.

The road to the Vanderbilt Cup changed almost annually.

The race did not return to the streets of

www.vanderbiltcupraces.com The northern leg of the new route was

Old Country Road, the eastern leg was Broadway (the modern Route 107),

the southern leg incorporated sections of the new Motor Parkway, and the

western leg was (I think) along or near Glen Cove Road.

The grandstand was on the southern leg, and - unlike in 1904

- the course was driven counter-clockwise. The revised course did not cross any

LIRR tracks, and there were no "controls."

A shorter course meant fewer roads to close, fewer legal

disputes, etc. The reason

most often given for shortening the course was that having more and

quicker laps offered spectators a better experience.

From a single spot, people saw the cars more times and at shorter

intervals; there were few lulls. Attendance

each year topped one-quarter million. A

Different State of the Art The automobile now was a more familiar

part of American culture than in 1904.

Auto racing had acquired a broader fan base, one which was less

interested in exotic cars. The

country's affair with stock-car racing had begun.

Racer versions of production American cars now competed all over

the country, usually on ovals, driven by men like Barney Oldfield, whom

the public idolized.

Swiftly navigating a series of curves

now was appreciated less than pure speed.

Compared to road racing, both drivers and cars had to be agile in

a different way. Oldfield

embraced the change, and he took it to an extreme.

He had "observed" a Cup race "to see what he could

learn," but afterwards he returned to ovals and pure speed pursuits.

Eventually, he forsook sanctioned auto racing completely, opting

instead for one-man events, like speed record attempts, or one-on-one

challenges. Once, he even

raced a car against a biplane. Willie K must have been conflicted

about these developments. He

had wanted the excitement of road racing to promote innovative

engineering, leading to improvements both in racing and pleasure

driving. Now, the racing

public was understandably caught up in the moment, cheering for American

cars with familiar names. Deep

down, the cars they saw on the track were pretty much the same as the

ones in their own garages, right? A

Family of Races In 1909 and 1910, each race was three

races in one. The most

powerful cars competed for the Vanderbilt Cup, and raced for all 22

laps. In the same race, cars

with slightly smaller engines competed in the Wheatley

Hills Sweepstakes, but ended their race after 189 miles (15 laps).

Cars with still smaller engines competed in the Massapequa Sweepstakes, racing only for the first 126 miles (10

laps). This arrangement might seem to suggest

that the Vanderbilt Cup cars would have the course to themselves for

about 7 laps of the race, but that was not necessarily true.

The laps driven by the smaller, slower cars took more minutes to

complete. For example, when

1909's last Wheatley car completed 15 laps, the fastest Cup car had

only 4.5 of its 22 laps - 20% of the race - left.

For 80% of the Cup race, its driver had had to work his way

around the slower car(s). Carnage In both 1909 and 1910, the winner of

the Vanderbilt Cup was Harry Grant, steadily driving the ALCO Black Beast at average speeds well over 60 mph.

In the public eye, however, casualties ultimately overshadowed

the racing achievements of Grant and the other participants. Unlike the 1904 race, the 1909 contest

incurred no fatalities. However,

two Wheatley Sweepstakes

competitors had major accidents. Both

crashed into telegraph poles while rounding the Massapequa Corner, with

one of the cars also breaking a spectator's leg. 1910 was much worse.

In Swiss driver Louis Chevrolet (yes, the

man after whom today's Chevrolets are named) competed in 1909, scoring

the fastest lap at 76.3 mph, but his Marquette-Buick broke down, and he

did not finish. He and the

car returned in 1910.

From Wikipedia Chicago Daily News negatives collection, DN-0003451 Courtesy of the Quickly taking the lead, he was forced

to pit by a magneto problem. Once

back in the race, he again worked his way into first place.

On the fourteenth lap, the Marquette-Buick hit a rut in

modified from Google Maps image The night before, there had been two serious

non-race accidents on The stigma was too much to overcome.

In subsequent years, the event went to *** Another

Vanderbilt's Races In 1936 and 1937, George Washington Vanderbilt,

Willie K's nephew, sponsored races on a course built on the Roosevelt

Raceway grounds. A new cup

was won, one year by Tazio Nuvolari in an Alfa-Romeo prepared by Scuderia

Ferrari, and the next by Bernd Rosemeyer in the legendary

Auto-Union.

Bernd

Rosemeyer driving Auto Wikipedia

(Italian Edition) Public reaction was lukewarm, and the series was

discontinued. *** Epilogue Before closing this installment, let's look ahead. American and European interests in

racing differed. A Barney

Oldfield, for example, had no interest in driving cars around a twisty

course full of corners; he wanted to go as fast as possible.

Most European drivers thought (mistakenly) that there was no

challenge in racing on ovals. The

right kind of man, however, might be sufficiently open-minded and

creative to find ways of fitting together pieces of both worlds. In the next part of the story, we

follow American racing as it branches out, and we also follow the career

of one man in particular, Mike Caruso: born in

Mike Caruso in the car he built in 1929 for American sprint races, utilizing a British Riley engine www.carusomidgetracing.com/racing-photos.html "Exotic car" purists would cringe

if they looked back to the beginning of this article, and saw driver

Johnny Duncan in Mike Caruso's midget #6.

To make this car, Mike did something truly impressive (and

perhaps to some, sacrilegious): he sliced the block of an 8-cylinder

Bugatti engine in half, and rebuilt it into a 4-cylinder racing engine. *** Sources Information As always, old newspapers from the Of special note is the 1904 race map

from the *** Howard Kroplick's comprehensive

website at www.vanderbiltcupraces.com

proved invaluable for helping me piece together the many disparate -

and sometimes conflicting - news reports which I found elsewhere, and

also for filling in some otherwise unfillable gaps.

Note that within the website, one can search for specific topics,

including Mr. Kroplick also is the author of a

book filled with great information about both Willie K and the races: Vanderbilt Cup Races of Long Island, published as part of the Images

of Sports series by Acadia Publishing. *** A fascinating set of 260 images of the

1904 event exists online in the Digital

Collections of the Detroit Public Library.

To browse through them, search for 1904

Vanderbilt Cup Race on the website at https://digitalcollections.detroitpubliclibrary.org/

And yes, one also can search for images of other years' races. *** The factual information in this article

about Michael Caruso comes primarily from Brian Caruso's excellent Caruso

Racing Museum website, which also is credited as the source of two

of the photographs used above. It

can be found at www.carusomidgetracing.com *** Images Again as always with Ancient Hixtory, almost all the images included in this article have

been digitally modified for various reasons (improved contrast, file

size considerations, and the "removal" of the most

egregious of the defects, such as dust, stains, tears, etc.).

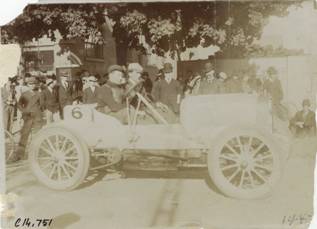

No attempt was made to change the purport of the images. An extreme case was the photo of driver

Herbert Lytle and his mechanician, sitting in the Pope-Toledo, which

appears at the start of this article.

It is a composite of images from two damaged prints in the

Detroit Public Library collection which was mentioned above: C14,751

and C14,797 of the Nathan

Lazarnick Collection. Here are the original images, followed

by the combined / edited result:

*** That's

all for now; more racing to follow in April!

|