|

MAY 2021

|

|

|

|

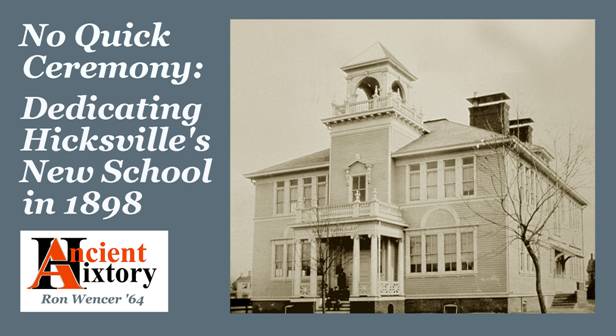

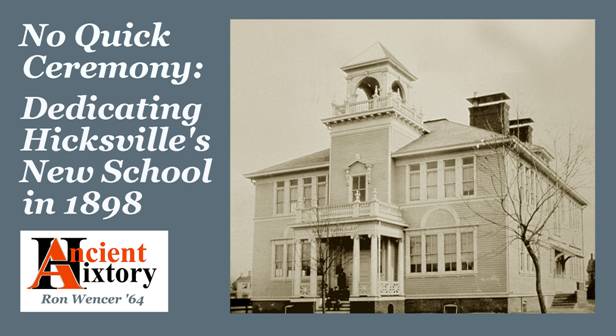

Union

School, Hicksville, as it stood 1898 - c.1908

The

image above was derived from two online digital images in

the Hicksville Public Library Collection at

New York

Heritage.

The first bears identifier M1616; the second (no identifier

listed) is essentially a mirror image of M1616.

|

During 2020 and 2021, numerous dedication

ceremonies have been deferred because of the pandemic (e.g., that of

Hicksville

's Vietnam War Era Memorial).

In contrast, back on January 3, 1898, nothing impeded the

dedication of

Hicksville

's new school building on

West Nicholai Street

. Moreover, those who

attended the ceremony that day "got their money's worth."

Before being given tours of the building, they heard a number of

speeches, enjoyed several musical performances, and listened to more

than a dozen students recite declamations,

which were a hallmark of scholastic ceremonies in the nineteenth

century.

|

***

|

|

Background: Declamation

|

From the beginnings of democracy in ancient

Greece

, societies who proclaimed or elected their leaders wanted their people

to comprehend the art of rhetoric

- the ability to persuade others through words and argument.

If rhetoric prevailed, then the vote of the populace might be

swayed by good ideas, not by personality or bribes.

Rhetoric did not always prevail, but in the history of Europe its thread

ran from

Greece

to

Rome

, through the Renaissance, and eventually into the modern era.

Along the way, over the centuries when most people were

illiterate, making a speech was the only tool by which ideas could be

presented to the masses. Certain

ways of formal speaking in formal settings became standard, which

resulted in an emphasis on teaching declamation

- a rather theatrical manner of speaking, which (in theory) engages

the audience by using physical gestures, and by carefully modulating

one's voice.

To us, this emphasis on how to speak one's words, rather than on

choosing them, may seem a bit silly.

But in the Victorian era, Declamation was taught early, even in

the lower grades of elementary school.

There were established age-appropriate readings, often in the

form of poems, to be declaimed by children.

For older children, these readings sought to evoke a noble

sentiment; for younger children, they evoked simple sadness or joy.

All of them tried to promote morals and proper social behavior.

The idea was that by learning early how to hold the attention of

an audience, a child might grow up to someday be a respected orator,

like William Jennings Bryan. Material

to read was in such demand that by the 1880s, for twelve cents one could

order by mail one of the several volumes of Standard Recitations by Best Authors from a publisher in lower

Manhattan

.

The following piece - I cannot in good

conscience call it a poem -

was read at the school dedication on

Nicholai Street

by Richard Sutter, 12, son of local stone mason Daniel Sutter.

It had appeared in the Journal

of Education for May 21, 1896, where it was printed alongside an

article called "Teaching Children to Think."

Some

Hicksville

educator had likely seen it in that journal, and set it aside, to be

declaimed by a student on some future suitable occasion.

It is understandable that the reporter

characterized the audience for the event as German.

The influx of suburbanites was still more than a decade away; for

now, almost all the village's officials, stores, employers, and clergy

bore German names. As

we'll see, the children who participated in the program all belonged

to German families as well. Note

that the Hicksville Band was a

marching brass band, and it fit right in, happy to oom-pah

and parade whenever it was given the chance.

It may be worth noting here that in 1898, the

United States

still had no official national anthem.

In this era,

America

- the melody of the British God

Save the King / Queen, but with the lyrics that began with the words

"My Country Tis of Thee..." - typically served in that capacity,

and it did in this case.

More noteworthy is the reference to Mary

Forgie. Local history

sources tend to gloss over the details of village's early efforts to

educate its children. Even

the Evers' Images of America book about

Hicksville

includes references only to early schoolmasters (all male), but names no

women who taught in the village's early Germanic years.

I regret that the Eagle's article gives us none of Mrs. Forgie's insights about

her experiences back then.

So that she may be a little less forgotten,

I have done some preliminary research into her life, which I include in

a brief Appendix at the end of

this article.

With the conclusion of the speeches, one

might think that everything that had to be said up front had been said,

and that a formal tour of the new building could begin.

That was not the case, however - after all, even Super Bowl

fans seem to think that a half-time show is necessary.

In this instance, the "half-time show" consisted primarily of 15

carefully rehearsed student recitations, each complete with declamatory

gestures and exaggerated facial expressions, of well-worn writings that

were didactic, and often joyless. Allowing

on average six minutes for each speaker to rise, walk forward, declaim,

accept applause, and return to a seat, we can assume that the

recitations in total took at least 90 minutes to complete.

|

|

|

The

Brooklyn

Daily Eagle, January 3, 1898

|

The declamations were punctuated by musical

performances. The first of

the latter was a piano rendition of Marching

Through Georgia, which would have stirred the audience, amongst whom

were a number of Civil War veterans (none of whom, one hopes, had worn

gray and fought for

Georgia

). There was a solo of The Star-Spangled Banner, sung by Jennie Hahn, 10, daughter of

merchant John Hahn. Also on

the program were another piece (unnamed) on the piano, and two numbers

played by the band. The

first of the latter was Red, White

and Blue; so many pieces of music have used these words as a title

or subtitle that one cannot be certain which of them was played.

The second was Listen to

the Mockingbird (if I am not mistaken, in the 1960s television

series The Prisoner, this was one of the recurring pieces of

"uplifting" music played in The Village).

Note that the pianist for this part of the dedication, Blanca

Kreuscher, was not local; she was part of a well-known German family

that owned a hotel in the Rockaways.

Fortunately for the reader, I have not located the texts of every item

that was declaimed, and thus I can inflict only a few more examples on

you. The first was performed

by Adam Lauck, 14, whose mother was a cutter of silver leaf.

He had the misfortune of presenting this long and

over-sentimental item:

|

|

|

The

Speaker's

Garland

, edited by Phineas Garrett

Volume II, 1892

|

Andrew Heberer, 10 years old, and son of

the storekeeper of the same name, got to read this version of the old

grasshopper-ant theme:

|

|

|

Delightful

Stories of Travel at Home and Abroad etc.,

edited by Allen E. Fowler, 1895

Part VI Elocution Exercises

|

You may have noted that the above rather

cautionary tale was included in an anthology of supposedly

"delightful" stories. Similarly,

J. Ofenloch (who was either John or Joseph, both about 11 years old and

sons of blacksmith Philip) got to read The

Contrary Boy, a painfully long tale of a spoiled little fellow,

printed in an anthology from 1853, which somehow was called The

Favorite Story Book, or Pleasing Sketches for Youth.

I am profoundly grateful that when I was 11, I was not forced to

read such a thing - I would have been compelled (and ready) to argue

with my teacher that the following excerpt, and in fact the entirety of

the piece, has no place in any collection of "pleasing sketches."

|

|

|

One

of the more upbeat portions of "The Contrary Boy"

The

Favorite Story Book, or Pleasing Sketches for Youth

edited by Clara Arnold, 1853

|

|

***

|

|

Inspection (i.e., Guided Tour) of the Building,

and Then the School Board Kicks Back

|

|

|

|

The

Brooklyn

Daily Eagle, January 3, 1898

|

Reading the above, one wonders if the

length of time devoted to student recitations had anything to do with

the fact that 7 of the children chosen to recite were offspring of

members of the School Board.

Within a very few years, as City dwellers

began buying new homes in anticipation of the railroad tunnels that

would make commuting realistic, the Union

School would become as overcrowded as its predecessor had been.

Even with the second building on

Nicholai Street

, which effectively doubled its capacity in 1910, the school would

remain overcrowded until the 1920s, when

East

Street

School

and the Junior/Senior High School

were constructed.

This growth in demand should not overshadow

the magnitude of change which the 1898

Union

School

represented for

Hicksville

. The building was large for

the immediate needs of the day (i.e., only 60% of the rooms were used at

first). Its large window

area, compact design, and clever touches (e.g., the convertible

classrooms/assembly area) were up-to-date for a rural school, and as

built, it was a rather handsome building.

The School Board members were entitled to indulge in a little

mutual back-slapping after the dedication ceremony.

If only they had been willing to cut short those declamations....

|

***

|

|

Appendix: A Brief Look at

Mary Amelia Brierly

|

Mary A. Brierly - later Mrs. Mary A.

Forgie - was born in 1839, in

Washington County

,

New York

, several miles east of

Glens Falls

. Her father was a shoemaker

from

Michigan

; her mother had been born in

Canada

.

She taught in at least two places: in the 1870s at the Union School in Hicksville, and around 1880 at the Academy

at

Glens Falls

.

|

|

|

Glens

Falls

Academy

, c.1880

Collection of Chapman Historical Museum

https://chapmanmuseum.pastperfectonline.com

|

She also may have taught elsewhere on Long

Island: at the time of the 1870 U.S. Census, she was living in the

Township

of

Oyster Bay

and working as a teacher. This

would be three years earlier than the newspaper account of the

Dedication ceremony states she had taught at

Hicksville

.

In

Glens Falls

, on May 13, 1884, she married a widower, one John Forgie.

As early as the 1850s, Forgie had worked in

Hicksville

, selling real estate and conducting estate auctions.

He must have had a curious, active mind, for in 1876 he was

granted a patent for a new type of propeller to be used on boats and

ships. In the 1890s, he

ventured into the metal-beating business, opening a shop on a property

near

Jerusalem Avenue

and

Newbridge Road

. It manufactured no gold

leaf, but it did produce silver leaf, and also something new: aluminum

leaf. The latter was thought

quite desirable for applying to the edges of the pages of bound books,

as unlike silver, aluminum would never tarnish.

After returning to

Hicksville

, Mary became a respected and well-liked member of the community.

She was remembered fondly by her one-time students, who by now

were active in business and local government.

In the mid-1890s, she was likely the only woman who sat on the

committee that determined how much tax-based funding the village's

School Board would receive to build and operate the new school.

She also was active with many charities, especially ones that

helped young children. When

the Spanish-American War began, disease ran through the troops quartered

at nearby Camp Black in Garden

City. Mary regularly made

the trip to the camp to "look in on the boys" and bring them little

gifts.

Life became hard for her after her husband died.

During his final illness, he had changed his will, which laid the

groundwork for legal proceedings that would pit Mary against the

children from his first marriage. The

children won, and she soon was nearly penniless.

She tried starting her own silver leaf business, but her age and

health did not permit her to succeed for very long.

Major cancer surgery in 1904 led to a slow and only partial

recovery; in 1907 she moved back to

Glens Falls

to live with a niece. At

that time, the people of

Hicksville

appreciatively gave her a send-off, including a financial gift in honor

of her years of kind service to the village.

She died in 1909.

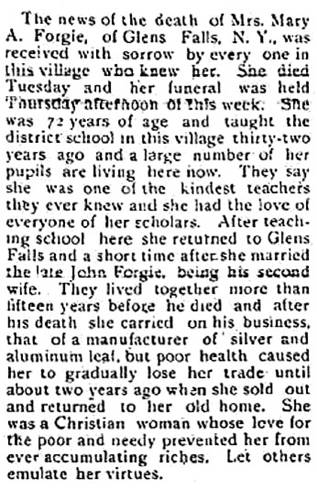

Three days later, this tender note about her appeared in the Long-Islander:

|

|

|

Huntington

Long-Islander, March 19, 1909

|

|

*****

|

|